Charles de Bériot, violinist, composer, teacher, philosopher, artist, died on either 8 or 9 April 1870. This sesquicentennial has sadly been eclipsed by the 250th anniversary of Beethoven’s birth, both of which have been recently pushed aside due to the worldwide Covid-19 epidemic. While most of us are currently spending our days at home, I wanted to draw attention to this remarkable musician who made an enormous contribution to the history of violin playing. His significant catalogue of compositions and pedagogical works (somewhere between 150 and 200 works), most importantly the five volumes of his violin method, have lost popularity with the passage of time and sadly most young violinists today only know his name in association with the handful of pieces which have been included in the Suzuki Violin Method.

Even the life of this remarkable Belgian was eclipsed by the tragic life of his first wife Maria Malibran. While the latter has been the subject of a large number of books and articles, the details of de Bériot’s life have scarcely been researched, his entry in the Grove Music Online is a mere four paragraphs and only includes a selective list of his works. In Belgium his importance has been eclipsed by the generation of his followers Henri Vieuxtemps and in turn Eugène Ysaÿe. Inhabitants of Brussels may associate him with his two houses which have since become town halls for the regions of Ixelles and Saint-Josse-ten-Noode, both of which were not only his homes but centres of cultural life for the capital.

While we have a rather significant collection of items which belonged to Maria Malibran in the Brussels Conservatories Library, RISM only lists 10 autograph manuscripts of de Bériot. I believe the nachlass of de Bériot was passed down through his son Charles-Wilfrid de Bériot and is most likely in the possession of a family of noble descent in France. This collection was reported to even contain philosophical writings by de Bériot!

As I am writing this the cemeteries of Brussels have been closed and I am unable to make another pilgrimage to de Bériot’s mausoleum. I am inspired to continue sharing interesting facts from the life of this amazing musician and 19th century personality. If you are a violinist, why not look up a work of de Bériot on IMSLP and pay a small tribute?

In today’s blog post I have translated, together with the help of Mary Bardet of the University of Birmingham, a lesser known early biographical sketch of de Bériot. The original text of this article is in italics, my commentary on it is in bold between brackets.

Let me first leave you with the closing remarks from de Bériot’s third volume of his violin method, which I leave in the original French:

Par métaphore : L’art représente à l’imagination un arbre qui s’élève dans l’immensité et dont la gloire couronne le faîte. Chaque artiste a pour objet d’en atteindre le plus haut point. Les branches de cet arbre sont les divers genres qui au lieu d’entraver l’artiste dans sa marche, lui font de leur obstacle un point d’appui. Mais celui qui cédant à la disposition de sa nature s’écarte du centre pour suivre une de ces branches dont l’accès lui semble plus facile, se trouve engagé dans l’impasse d’une manière. L’autre au contraire qui s’attache avec amour à ce milieu où viennent converger toutes les nuances de l’art sait en faire sa substance et fortifié par elles, il porte son talent vers les régions infinies de la perfection.

Galerie de portraits d’artistes musiciens, du Royaume de Belgique, Brussels, V. Deprins, c. 1843

There are men whose name alone acts as a talisman against indifference and serves as an absolute guarantee of success: if they keep to themselves, we complain about it, we ask for them; if they perform we are moved, we rejoice, they stir up a sense of inspiration, which we seize eagerly, savour with delight. Charles de Bériot is one of these fortunate men; whether he is performing or composing each act is a veritable event in the musical world and becomes a new triumph for himself. But here at least the public’s sympathies are fully justified; who else but De Bériot has known how to deploy the rare and precious faculties of virtuoso and composer that together make up an exceptional artist? Who else has known how to build their reputation on a better foundation? He possesses solid virtues that fear nothing from vagaries of fashion, and with which, whatever happens, he will always inspire admiration.

BÉRIOT (CHARLES-LOUIS DE) [De Bériot’s name was always given as Charles-Auguste.], born in Leuven on 20 February 1802, is descended from an old and well-regarded family. At an early age he lost both his parents who were members of the nobility [While we do not have information about de Bériot’s parents we do know that his uncle Joseph de Bériot was mayor of Leuven from 1800 to 1804. De Bériot’s great-grandfather was a nobleman from Sevry, Belgium where he is buried. The family is of Spanish descent. De Bériot’s noble lineage would be recognized officially in 1853.]; but he soon encountered a musician from his hometown, by the name of Terby [The name of De Bériot’s first violin teacher was Tiby as can be seen by the dedication of his opus 1.], who would become both a second father and teacher to him and who zealously cultivated his musical talents. He progressed so swiftly on the violin that, at barely nine-years-old, he earned the admiration of his compatriots for the way he performed Viotti’s concerto, in a minor, at a public gathering. “Nature has given De Bériot” said one Belgian musical expert (Fétis, Biographie universelle des musiciens, vol. II, Brussels, 1835) “the feeling for an exquisite intonation which fuses in his playing with a naturally elegant taste. Blessed with a meditative nature [De Bériot was deeply interested in philosophy and especially the method of Joseph Jacotot who taught at the university of Leuven from 1818 to 1830.], and having no immediate role model to emulate, he searched by himself for the principles of beauty, the notions of which he could only obtain through his own spontaneous actions. [Fétis often emphasized the ingenuity of De Bériot. While this may well have been completely true, stressing his originality also increased the independence of the Brussels Conservatoire’s violin teaching as opposed to the Paris Conservatoire.] A good disposition, both moral and physical, plus a good start in education, quickly led De Bériot towards gaining a truly remarkable talent, one which only needed contact with other types of talent in order to gain polish, and by coordinating all parts concerned, allowed it to take on a definitive character.”

At the beginning of 1821, De Bériot left for Paris where he firstly played for Viotti, director of the opera at the time, who gave him great encouragement. [In a letter to his childhood friend Eugène Fontaine dated 13 July 1821, De Bériot actually says that he met Viotti for the first time after having auditioned for the Paris Conservatoire.] He then entered the Conservatory, under Baillot, but only stayed a few months, preferring to succumb to his natural instinct, to his own particular genre, rather than bending to fit in with set scholastic forms. [Viotti’s advice to De Bériot, quoted in the letter mentioned above was, “Try to listen a lot, and take what seems good to you, be like a bee and you will create a genre.”] Consequently, he had the opportunity to perform in several concerts where he wrought great success, both as a performer and a composer.

De Bériot’s fame reached England so he made his way there and, after a successful stay in London, he travelled around all the major cities of Great Britain. His success there was even greater than that in Paris and consequently he accepted several proposals that would involve subsequent trips to MEETINGS, or music festivals that cropped up each year sometimes in London or Manchester, or at other times in Birmingham or Liverpool.

On returning to his home country De Bériot received a salary of 2000 florins from King William [William I of Orange king of the Netherlands of which Belgium was then a part of.], naming the young artist first solo violin in his private music ensemble. He lost this position during the revolution of 1830; but if we are not mistaken, it was given back to him a few years later by the new king. [De Bériot did indeed receive the title of first solo violinist to King Léopold I of Belgium.] Additionally, he was named a Knight of the Order of Leopold, in 1837, and earlier had received the Iron Cross as author of the national song: LA MARCHE BELGE. [De Bériot’s work is entitled “Marche des belge chant patriotique”.] He was a member of several musical societies, including amongst others the famous St Cecilia of Rome. [The Accademia Nazionale di Santa Cecilia.]

Having become an intimate friend of Madame Malibran [Maria Malibran née Felicitas Garcia Sitches was perhaps the most famous member of a large family of musicians which included Manuel Garcia and Pauline and Paul Viardot. De Bériot was also a distant cousin by marriage to his colleague Hubert Léonard.], De Bériot travelled with the famous singer in Italy and England. In Naples, where he performed at a concert held at the Saint Charles theatre [Teatro di San Carlo], he was lauded with an enthusiasm rarely shown in this country towards instrumentalists, Italians generally choosing to reserve this kind of enthusiasm for their preferred predilection: the voice. On 29 March 1836, De Bériot married Madame Malibran in Paris; returning to Brussels a few days later, the two famous artists gave several concerts, of which the benefit for the Poles (at the Temple des Augustins) [The Temple des Augustins no longer exists in Brussels but its facade can still be seen on the Église de la Sainte-Trinité in Brussels. The church served as a concert hall for the conservatoire until the erection of its own building in the late 19th century.] would prove to be the most brilliant and productive of all. The couple set off to England for a festival where they had been asked to perform and which was due to take place in Manchester in September of the same year; but alas! they would not travel back to the continent together. Madame de Bériot-Malibran sung in the quartet of FIDELIO [Beethoven] and had agreed to a duet of ANDRONICO [Mercadante]with Madame Caradori [Maria Caterina Rosalbina Caradori-Allan]. The thunder of applause that had welcomed her had scarcely died down when this celebrated artist, moments ago so brilliant, so animated, fell unconscious. [Maria Malibran died due to injuries from falling from a horse in July of 1836. Among the items in the Malibran collection in the Brussels Conservatoires Library is the horsewhip said to have been used that fateful day.] Transferred back to her hotel, she received medical attention that would prove to be too late, she died on 23 September. Her remains were returned to Brussels several months later and placed with great pomp and circumstance in Laeken cemetery, where her husband had erected a mausoleum. [Maria Malibran was buried in Manchester on 2 October 1836. At the end of November her mausoleum was being built and she was reinterred there on 4 January 1837. The director of the Brussels Conservatoire, François-Joseph Fétis, delivered one of the addresses as he would at the funeral of Charles de Bériot in 1870. The students of the conservatoire also performed during the service.]

De Bériot, cruelly heart-broken, was not heard from during the fifteen months following his wife’s demise; he only decided to reappear in public for a large charity event: a benefit concert for the poor given in Brussels’s city hall on 15 December 1837. [De Bériot performed his 1st and 5th airs variées. His sister-in-law Pauline Viardot née Garcia also sang during the concert.] Since then he has given several concerts both in Belgium and during subsequent trips to France and Germany. In Vienna he received seven encores for his TREMOLO [Le tremolo caprice sur un theme de Beethoven, opus 30. The term tremolo should not be confused with the modern technique. De Bériot’s tremolo was a type of bariolage bowing.], amidst the liveliest enthusiasm ever given to an artist. What can we add to this! [This concert was also in the company of Pauline Viardot and occurred during a European tour in 1838.]

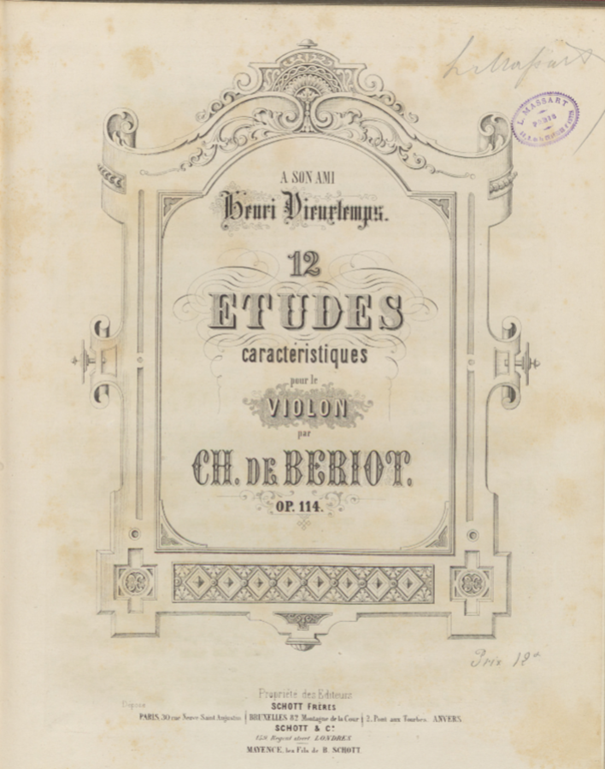

De Bériot’s oeuvres are divided as follows: Dix Etudes, ou caprices, premier livre d’étude. – Six études brillantes, deuxième livre d’études. – Six caprices brilliantes. – Three concertos. – A trio on the motifs of Robin des Bois. – Eight Airs variés, among which the famous Trémolo. – Twenty-two pieces entitled: Duos, or Fantasies, or Souvenirs, or Variations, or Nocturnes, composed on the motifs of operas or original themes, with Labarre, Osborne, Herz, Benedict, Schoberlechner and Wolff.

When we say that De Bériot’s compositions are expertly organised to brilliant effect, with a full, bold daringness, wherein the accompaniment is treated not only with taste but with expert knowledge, the counterpoint perfectly executed, the repeats prepared with marvellous address, we will only have pointed out the most vulgar of qualities; however we would be incapable of attaining the individual essence of the master, this moving charm, this warmth which exudes a nervous energy and yet remains contained, this wonderful feeling that marks each of his works, and to which his performance alone holds the secret.

As for De Bériot’s playing, nothing could be more perfect. Everything is so round, so pleasant, so blended together, so exact, so precise that nothing else could even come close. It must be said: it is not simply the bow strokes, his magnificent double cadences and trills which uplift you, it is not simply that one listens to him open-mouthed, but that we hear them with a soft, indelible inner pleasure. Everything is song, everything is sound. None of this “tour de force” could be classified as charlatanism; everything is noble, dignified, calm and perfect. When we examine the bowing of this splendid virtuoso, we can find nothing pedantic, nothing artificial, nothing stiff, nothing affected; but the greatest lightness, the most incredible ease, and always the purest sound, the smoothest, whether he is crying an elegy from his adagio, or singing the lively, crisp poetry of his rondo, or else playing his variations always so flowing and charming, or perhaps modulating the vibrations so gracefully interlaced into his tremolo. [It is not clear whether the author is referring to vibrato or another effect.] No other virtuoso has ever produced a double cadence with more body, more polish, more depth, of lightness and at the same time expression. De Bériot’s playing is all sentiment, total perfection. When you have heard this magical bow, you can no longer be surprised that at the Manchester festival the English didn’t want to cancel his performance, whilst at the same time his wife, the queen of song, this Marie that we cannot forget, lay on her deathbed.

There was only one opinion in the French art world, to name de Bériot violin professor at the Paris conservatory, a position left vacant following the demise of Baillot. [Pierre Baillot died in 1842 and there was much speculation on the part of the French and Belgian press as to who his successor would be. At various times it was announced that De Bériot had accepted or rejected the position. De Bériot ultimately declined and the position was split between the Belgian Lambert Massart and the Frenchman Jean-Delphin Alard.] “It would be desirable” the NATIONAL reported “that an artist as eminent as De Bériot, whose name has become European, should be the successor to the greatest violinist of our times and these circumstances, which only occur once in an artist’s career, should lead him to accept such a noble heritage.”

“It would take nothing less than Mr. de Bériot’s exceptional talent to silence the genuine displeasure of seeing a foreigner occupy such an important position in a national establishment.”

The musical art world can be reassured, De Bériot will not be leaving his homeland, he is staying amongst us; because there is a possibility of him founding a special class for the violin at the Brussels Conservatory, where he can train students worthy of his reputation and of that of Belgium, one which he himself quickly raised to prominence in the musical field. [In 1843 De Bériot was hired by the Brussels Conservatoire to start a “classe de perfectionnement” for violin, a position he would hold for nine years and which solidified the reputation of that institution for violin teaching.]

© Text, Richard Sutcliffe 2020

© Translations, Richard Sutcliffe & Mary Bardet 2020